Arvida Byström: Counter Image

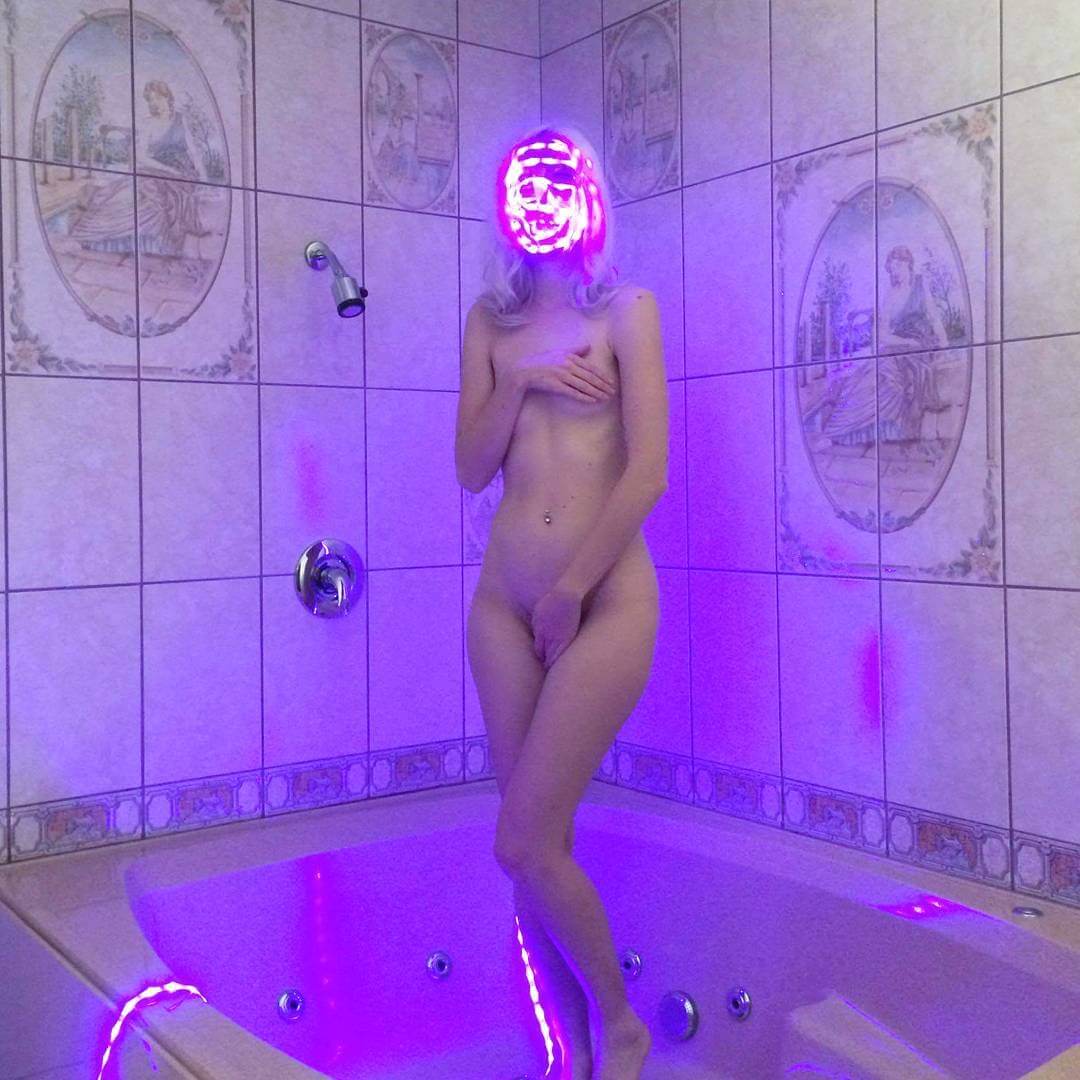

The work of the artist, photographer, and model Arvida Byström radiates self-confidence. On her Instagram account, she expresses herself in a rich variety of poses and settings. The exploration of her own body by taking selfies led the artist into questioning our beauty standards and to find new forms of self-expression. She appears with an unshaved pubic area, without make-up, and showing cellulite. Byström often counters social female beauty standards. The images she posts on her Instagram feed are artworks as well as commercial photographs. Byström’s double role as influencer and artist raises a discussion regarding the differences between a normal selfie and one considered as art. In her work, Byström draws parallels to art history. She includes vanity motifs like flowers, fruits, or mirrors that are referring to the transience of earthly goods. The “young woman” – in this case Arvida Byström herself – is traditionally also considered a vanity symbol. By depicting herself as a nude, the artist highlights her female rights because women artists have only been granted access to nude studies after a live model since around the beginning of the 20th century. Before, the female body was depicted by male artists. Byström often works with mirror selfies and includes her camera, her tool, in the photo to emphasize her authorship: she is in control of her self-image and owns the rights as she is also the photographer. Arvida Byström’s work is provocative and political. It speaks to feminist culture as well as to art history, and at the same time questions the values of both.

Biography

Arvida Byström (b. 1991 Sweden, Stockholm) is a digital native with an intrinsic relationship to pink. Exploring femininities and its complexities, often tied to online culture, she travels in an aesthetic universe of disobedient bodies, selfie sticks and fruits in lingerie. Her photography and endless Instagram scroll has been in art shows all over the world as she starred both behind and in front of the camera of numerous influential brands and magazines like . Adidas, Gucci, Absolut Vodka, Dazed media, i-D magazine, H&M, Topshop, 10magazine, Numero Berlin, or Vice magazine. Her selected solo exhibitions Inflated Fiction (Fotografiska, Stockholm, Sweden, 2018), Cherry Picking, (Gallery Kranjcar, Zagreb, Croatia, 2018), Wifi or wife (Bon Gallery, Stockholm, Sweden, 2014). Selected group exhibitions: Link in Bio,(Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig, Germany, 2019), Bodyfiction(s) (Musée national d’histoire et d’art, Luxembourg, 2019), Pics or it didn’t happen(Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium 2017).

Interview with Arvida Byström (Sweden)

by Tina Sauerlaender (Berlin), April 17, 2020

Tina Sauerlaender: Hello Arvida! On your Instagram account, you post selfies and self-portraits. Is there a difference for you?

Arvida Byström: I would say that I work with selfies, but selfies are a form of self-portraits. Selfies are a type of self-portrait that is generally taken with a phone camera. As soon as you use a "proper" camera, it is considered just a self-portrait. I did self-portraits with my normal camera before selfies was a thing so I always been drawn to the self-portrait as a medium.

TS: One of the reasons why artists work with other cameras is their higher resolution. Is this the reason why you use other cameras?

AB: I come from working with other cameras, but I do like the texture of the phone photo. I like to play with that because of the cliché with film grain from a film camera that is seen as classy, but digital grain hasn't gotten that status yet. I like that when you get close to it, you can see the grain, because phone cameras get a very specific kind of texture, which I think is interesting.

TS: How would you describe the way of representing yourself in your works?

AB: I don't think there is necessarily a coherent thought. I am me and I have the baggage that I have. Not that I am from performance art, but I am aware of performance art and I like to play with it and play with the body. There are certain selfies I put in my art shows and then there are selfies that I take for other reasons.

TS: Would you say that IRL Arvida and online Arvida are the same person?

AB: Arvida is my middle name. My friends and family call me by my first name, which is Emma. Arvida is a very natural extension of how Emma is. How Emma acts privately in small groups or with someone close is different than Arvida, but not very different. It is more like if you would go on a stage or step into a very big crowd.

TS: You often use different shades of pink in your work. Could you tell me more about your use of it?

AB: Pink has always been very important in my life. I adored it since I was a kid and had a pink phase where I only dressed in pink when I was 13 or 14. And I often had pink hair. When I found Tumblr, I started working with pink more consciously. Obviously pink is something that it's both feminized, and it's also something that is attributed to childhood. And I felt red was stealing the spotlight from pink and red was considered a universal color. And pink was always just attribute of females. I would say that the rise of my Tumblr group and people like Molly Soda or Petra Collins are definitely been part of popularizing pink. And now, because of the millennial pink, I would say that pink has been co-opted. Now if you look at different commercials, you see kind of salmon, peachy shade of pink. Pink has become more neutral, even though it depends a little bit on the shade.

TS: The term hyper-femininity has been attributed to your work. What do you think about that?

AB: I guess femininity in itself is almost hyper because it is something very performed or something that we get taught from society. I think in terms of my work people call it like that because it is so in your face.

TS: How do you choose the selfies you show in an art context?

AB: I usually take selfies for a specific project. In general, I would say that my works are not totally defined. The line between me being an artist and me being an influencer is blurred. Some people consider my art less art, less cool, because I am also an influencer. To me, that means that the reality of being a real influencer is too low brow for the artworld which makes sense since the art world is trying to operate on being high brow. But you could compare my practice to Amalia Ulman’s performance Excellences & Perfections which was not real, it was purely an artwork. And that is why that project probably get higher status in the art world. On a personal level, I sometimes struggle with that, but also find this interesting and like to play with that.

TS: You engage both in self-portraits and in still life photography. How are these two genres related?

AB: Nude studies were not allowed for women 300 years ago. Back then, women were seen to be suited to only paint still-lifes and not human bodies. Still-life was considered among the lowest in the hierarchy of genres, unlike religious paintings. And today where women have taken over depicting their own bodies, it is questioned and looked down upon. Selfies, which is a genre tied to women, are rather considered low brow.

TS:In your installation for Bodyfiction(s) (Museum Cercle Cité and MNHA, Luxembourg, 2019), you use the sentence "You give her a selfie cam and then you call it vanity." Does this advert to women being accused of narcissism when taking selfies?

AB: It is an updated version of the John Berger quote "You give her a mirror and then you call it vanity.” There is an issue with the smartphone and all the apps and how it's accelerated our individualism and the strive for that individualistic way. You give people a flip cam and it is easy to take a selfie. Of course, people are going to take selfies. And that is not bad in itself. It's just literally made it easier to do so, so people do that.

TS: You often work with mirror selfies and include your selfie stick and camera in the image, why?

AB: I do love showing my tools, and showing it from a queer perspective. Queer theory is so much about showing who makes the work, so people can judge it from the perspective of who made the work. Another part of showing my tools is about the classic, fifty-year-old male photographer, who would stereotypically take, maybe with a Hasselblad camera, photos of beautiful women. All those men have a photo of themselves that's held into the mirror, holding the camera, showing off their expensive tool. And this kind of self-portrait is seen in such a different light from the mirror selfie. Which is exactly the same thing. But that kind of self-portrait has such a different weight than the feminine mirror selfie, or the young girl mirror selfie.